About the Author

Nic Tompkins-Hughes

Nic Tompkins-Hughes (BSW, MPA), is a social science researcher, community organizer and advocate. Nic identifies as transmasculine non-binary and uses they/them pronouns.

Visit Nic's LinkedIn for an overview of their academic and professional experience Here or the About Me page for more info.

Sections

Experiences of Transgender Adults Accessing Healthcare in Massachusetts

Experiences of Transgender Adults Accessing Healthcare in Massachusetts - Results

Over the course of the study, three central concepts emerged from the narrative data. The first resulted in a model of accessing and identifying trans-knowledgeable healthcare providers. The second identified aspects of experiencing safety and comfort while accessing health care, and the third indicated a general concept that participants experienced health care as a privilege rather than a right of all individuals.

Experiences Accessing Healthcare

Length of primary care relationship. Seven of eight participants reported having an existing relationship with a primary care provider (PCP). Of these, six had been established for about a year or more. Five of seven participants connected to a PCP reported having accessed their PCP for services within the last three months. The participant without an established PCP did report a recent need for medical treatment which required the support of a PCP, during that same three-month timeframe. The participant was held up when they needed access to specialist referrals or other ongoing services typically provided by a PCP, but which they were unable to access as a result of not having a relationship with a PCP. Without this relationship, patients must then rely on Urgent Care centers or Emergency Rooms for care. When discussing the options for accessing medical care due to an unexpected or urgent medical need, individuals consistently stated that without a primary care provider, the emergency room or urgent care was the typical option and two participants made comments about delaying care altogether due to fear. However, among individuals with a PCP relationship of approximately six months or more, the main concern was whether an appointment would be available within the time of need, and could they tolerate the stress of an urgent care visit if necessary. Among all participants, half (4 of 8) self-reported directly experiencing a transphobic or negative interaction based on their identity as a transgender person in emergency room and walk-in/urgent care settings. Participant Three shared insight on weighing the choice to delay urgently needed medical care due to the potential negative experiences and dysphoria:

"Usually the only times in the past that I’ve needed like, you know immediate care like that, have been something more serious or I’m genuinely concerned about something. And in that case, based on where I live, my only options are either an urgent care center or like literally a hospital, depending on how severe I deem whatever it is to be... instead, what ends up happening is usually the first reaction as a patient, as an individual, is if something goes wrong, the first thought that comes to mind is can this wait? Like, can I live, can I stick it out and set up an appointment for somewhere in the future or is this like life or death? That shouldn’t be the thought process, but that’s sort of how it is."

- Participant Three

Participant One on hoping they can build a relationship with a primary care provider:

"I don’t even really know how the transition process, works. Legally and all that stuff. Like of course I’ve watched people go through it, but I don’t really understand it. And when it comes down to that for me, I know at the point in my life, my family’s going to be gone. I’m not going to have a person like that. So, I want to create that relationship in the health setting so that I can ask those darn questions, because I’ve never had a chance to in my life."

- Participant One

Compromising Identity for Care. Some participants reported actively “pretending” to be cis-gender, in order to prevent discriminatory experiences while accessing healthcare. Participants could choose to disclose their identity and transgender status and out themselves immediately, thereby increasing the likelihood that they would experience some form of intentional or unintentional inappropriate and disrespectful questioning and/or interaction from a member of the medical team, up to and including “firing” providers due these instances, and/or delaying care as a result of preventing further experiences of discrimination;

Alternately, participants could choose to hide their identity, thereby preventing medical providers from making educated evidence based assessments of needs and medical treatment plans based on the known vulnerabilities of transgender populations, also preventing transition, and experiencing significant ongoing dysphoria during medical interactions – up to and including delay of care as a result of preventing this consequential dysphoria. Participant six spoke on choosing to let people believe they are not trans:

"Most people think I’m a butch lesbian. Because that’s generally how I passively sort of look, so when I go into an urgent care situation, I am using my given name, and pronouns, and all of that, and all the documentation that goes with it... I would say yeah, that is a choice I’m making. Particularly because part of it is I don’t want if I’m going to the doctor, to a doctor, for a stomach issue, I don’t want to go to the front desk, give them my name and things like that, and then hand them a driver’s license that doesn’t match and then have to deal with that."

- Participant Six

Primary Care Access Model

Internal and External Motivators

Participants were asked to explain how they came to be established with their primary care provider, which resulted in two specific motivations which were defined by the researcher as: internal drive and external drive to seek a primary care provider. Internal drive refers to the participants’ own internal motivations for seeking medical care through a PCP (5 of 7 participants), while external drive refers to circumstances such as insurance requirement, or the need for a referral to a specialist (2 of 7 participants).

Participants who indicated an internal drive for seeking medical care of any kind all identified the driving force as a need for transition related care, specifically hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or a physician’s certification letter to access surgical transition to ease experiences of daily dysphoria. This internal drive was referred to as being “urgent,” and participants also described battles with dysphoria and discrimination as drains on their mental health and overall wellbeing. Participant 3 on the implications of delaying transition related medical care:

"I wanted to definitely get an appointment set up as soon as possible, purely because I knew if I did not that I would be – end up putting it off for much further in advance, and it was something that I really wanted to make happen in my life, in terms of beginning that aspect of my transition. It was mostly for myself, that I needed to self-motivate, you know, to do that. And if I put it off any longer it wasn’t going to happen, because I struggle with a lot of mental illness and stuff, and it was the kind of thing that if I didn’t go for it, you know – set up an appointment within the month or something for example, it was just never going to happen and that was going to be worse for me."

- Participant Three

Of note, in total, 7 of 8 participants indicated that access to HRT or other transition related medical care is an internal motivator for seeking healthcare, regardless of their current connection with a PCP.

A key external motivator was finding and accessing care after aging out of a parent’s insurance, aging out of a pediatric practice, or not being able to receive trans-knowledgeable care from a pediatric practice. Participants described a gap in care coordination which resulted in a challenge for these participants in establishing care with a PCP as an adult, independently. Participant six illustrates this experience:

"I was still seeing my pediatrician, and she has always been very nice and helpful and just overall a very good physician, but I do recall that when I was trying to – first starting to explain to her you know what I was feeling transition-wise she didn’t really understand it. It was a difficult experience, not negative per se, she wasn’t not-accepting of it, or didn’t make me feel bad or unsafe or anything like that. But I do remember it being kind of frustrating, because I got the sense that for however long that she had worked as a pediatrician she didn’t really come across this that much, and didn’t know how to respond to what I was telling her. She was like not informed enough about trans experiences or identities or anything that that entailed, so it was difficult because as a patient you go to physicians to try to get their input and get help from them and have them sort of tell you what to do and almost go for guidance sort of thing. But then when it’s flipped and then you have to explain something to them it becomes kind of tricky and frustrating because you’re not quite sure how to approach the situation anymore."

- Participant Six

Method for identifying trans-knowledgeable medical providers. Among all participants, a unique process of identifying and vetting a new potential medical provider was reported following the participant’s internal drive to seek transition related medical care. Participants initially started with searches online focused on geographic location and transgender knowledgeability, determined by depth and extent of external/public facing trans-inclusive content they reviewed. Secondly, participants checked in on social media and with peers for references from individuals with similar needs and life experience (transgender, seeking transition related medical care or other specialized care, geographic location). Of note, three participants reported having been actively refused transition-related medical care from their existing primary care providers, in two circumstances this directly caused the patient to need to find a new PCP. Participant eight details the struggle of attempting to seek hormone replacement therapy through their existing PCP:

"I started at my primary care, and she wasn’t, she shot me down and said that she had never heard me talk about it before, and she didn’t feel comfortable treating me or sending me to an endocrinologist. So, I just stopped going, and then I called Fenway, and it took like four months out to get an appointment. So, then I got my first appointment, and then she had to see me three times before I could get a shot, so – and there, also it’s hard to get an appointment unless you really really need it. It took about, it took a full year to get on hormones after I started vocalizing it."

- Participant Eight

Participant two discussed how a friend’s social media post lead them to establishing care with a new provider based on feedback from social media:

"Before physically changing my name, transition, that was you know not fun that I would have to get mail in you know that said my old name and my gender and everything. This isn’t about me, but I have a friend, that he just got his name changed, and he’s already had all of his surgeries, he was looking into the final stages of phalloplasty, and the people the billing people sent them his name, his preferred name on the statement. He put it on Facebook, he was all excited about it, because they knew he was trans and they took that into consideration, and I thought that was a pretty cool thing."

- Participant Two

Lastly, based on the availability of providers geographically, and/or the limited availability of identified transgender knowledgeable providers, 100% of survey participants ultimately became a patient of, or at one point intended to become a patient of, Fenway Health in Boston, Massachusetts, regardless of their home location within the state. For several participants, the geographic limitation and financial costs associated with the burden of traveling to the Boston area were the largest obstacles to receiving trans-knowledgeable medical care, as the perception and reality both are that there is no such care outside of the larger city areas. Participant five outlined their challenges trying to find a trans-knowledgeable PCP outside of Boston:

"I have bounced around from one primary care to another. Either they won’t call me by my name and my correct pronouns, or they’re willing to but they’re all the way in Boston, and I cannot afford the gas, the high co-pay, and the time off work, and paying for parking. I have to choose between a healthcare professional that respects me but costs me well over $100 for a visit, or one that doesn’t respect me and makes me incredibly uncomfortable and calls me by my deadname."

- Participant Five

Additional findings of import regarding identifying medical providers were focused around geographic location, with participants from Western and Southeast Massachusetts (including Cape Cod and the Islands) reporting more significant barriers to accessing trans knowledgeable healthcare overall, of the following types: transportation access, financial/economic hardship including insurance incompatibility, and a high demand for trans knowledgeable providers resulting in long wait times to initiate care with a small number of available providers. Outside of trans-knowledgeable primary care providers, participants referenced that they would otherwise rely on endocrinologists as a specialist for transition-related medical care, or from local Planned Parenthood sites. As gender affirming healthcare services are offered at all Planned Parenthood sites according to their website, this creates some additional options for individuals in the Greater Boston and MetroWest Areas. However, as participant 3 expresses below, wait times are often long, and the Cape and Islands area continues to be under-served with no Planned Parenthood within 50 miles of most parts of Cape Cod:

"I was trying to go with Planned Parenthood initially because I had I have been a lifelong supporter of planned parenthood and I was trying to set up something with them, I think they have a branch in Boston. They were, they were just packed full and I think I came across that with a couple other places as well, where just like, there’s such high demand for it and so few places to go that the places I did find were absolutely booked through for months and months and months in advance. It was impossible to get an appointment with them."

- Participant Three

Establishing the relationship with primary care providers.

When asked “how comfortable did you feel initiating care with a new provider,” participants had a wide range of responses. Among participants who were referencing initiating care with a provider they knew to be trans knowledgeable (through internet searching or references from the trans inclusive community), 75% of participants used the word “easy” and half used the word “comfortable.” Even the one participant who stated they initially felt anxiety establishing care with a known trans knowledgeable provider stated that once they began the process, things became “easy and comfortable.” Participant two reported:

"What’s made it positive has been if they were educated on being transgender. Just in general. If they were- if they understood how to identify you, you know using your pronouns. If they understand physical transition at all because it’s been very positive when I go to my pcp and I don’t have to worry about anything. [They] know my gender and the surgeries I’ve had, and what that all means."

- Participant Two

Conversely, among individuals who were establishing care with a new provider, of whom they did not know if the provider would be trans knowledgeable or friendly, responses included: “scary” and “hard.” Participant one reported:

"Doctors make me very uncomfortable as a trans person, because – I just know how unaccepting the health field can be. So I just stopped... it was pretty nervewracking. Cuz it was the first time I was seeing a physician in two years."

- Participant One

One participant described circumstances where they utilized an assertive tone or strategy to overcome the likelihood of negative experiences. This included intentionally coming out to the first contact during the first interaction (often while calling to inquire about availability) and informing the first contact of the expected terms of interaction, to prevent the opportunity for misgendering. Assertive strategies were also mentioned by participants as a method of trying to prevent members of the medical team from using incorrect/birth names, also known as “dead-naming.” Participant four describes the choice to use an assertive strategy with the first contact at a new provider:

"I never changed my voice as part of the transition. So, I was running into a lot of issues on the phone with people calling me sir, and even if I told them what my name was, I would still get called Mr. LASTNAME. So I took a pre-emptive approach to dealing with people on the phone, where they would ask my name and I would tell them my last name is ___, my first name is ___, and I prefer to be called Ms. LASTNAME or Ma’am. So, I don’t even give them the opportunity to make that mistake."

- Participant Four

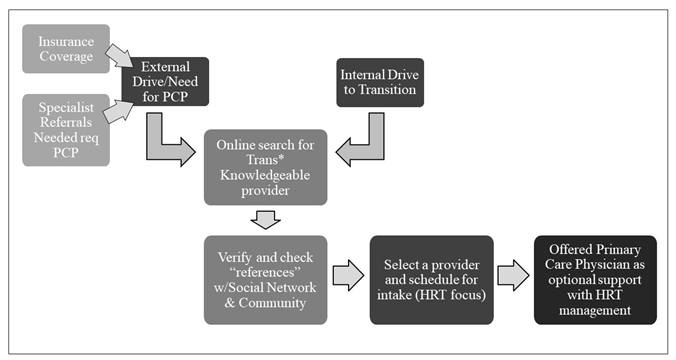

The following visual model was created which illustrates the process described above. Starting with both the internal and external motivators to seeking medical care of any kind and resulting in a relationship with a trans-knowledgeable primary care provider (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Primary Care Access Model

Note. The Primary Care Access Model depicts the flow of the process identified by survey participants. Due either to an external motivator such as specialist referral requirements or insurance coverage requirements, most participants sought care with a new medical provider in order to pursue medical and/or surgical transition related medical care. With the motivation generated from the external or internal drive, participants utilized online searches for transgender medical providers. Evaluation of public facing materials was key, but ultimately, obtaining “references” from others within the LGBTQ+ and Trans identified communities was a major determining factor in which provider was selected and contacted to initiate care. Primarily, study respondents were initiating care with a new provider specifically to pursue hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to ease dysphoria, typically provided through a specialist such as an endocrinologist. Once at the appointment and after reviewing the informed consent process, participants were offered the option of receiving routine healthcare and preventative care with a primary care physician within the same practice, offering both transgender specific medical care as well as routine preventative care, through the same provider. This resulted in an ongoing relationship with a trans-knowledgeable provider.

Experiencing Safety and Comfort While Accessing Healthcare

The participants identified experiences of both safety and comfort while accessing medical care. Safety was identified as one’s feelings and expectations of physical and emotional safety while accessing care. Comfort was identified as a more subjective perspective and experiential feelings of ease, confidence in the provider, and feelings of welcome and inclusion. These trends were most observable in the following aspects of the data, starting with self-reported incidences of transphobia as well as the types of observable signs of comfort and safety that participants reported. Participant six discusses how a positive and trans-knowledgeable first contact can positively impact patient access experience:

"The scheduler at the gender clinic here in my college town, I love her, she’s wonderful, every time I call she’s very knowledgeable about her job and about how and specially because I was a new patient and it was a new avenue of healthcare for me, and I didn’t know a lot of what I was doing, however she was very knowledgeable and very helpful. And she was very good at helping me get what I – about answering the question that I was trying to ask and not necessarily the one I was asking... she made sure to check in on things like name and pronouns, which I find especially important at a gender clinic."

- Participant Six

Defining Trans-knowledgeable prior to the appointment. For most participants, in the first interaction with the first contact, determinations needed to be made immediately regarding the trans-knowledgeability of a new provider, the safety of the setting and interactions, and the comfort the individual could reasonably expect from interactions with the medical team. This was described as being a decision made even within the first phone call to the office, with the initial search results and public facing online presentation of trans-inclusive information, or lack thereof, sometimes also disqualifying providers prior to first contact. The need to make an immediate decision regarding the safety and comfort of seeking care with a new provider was reported to also carry beyond the initial visit. Participant one reported:

"I’m an adult but going to the doctor’s is scary, and I wish that more people would be aware of that and be more sensitive to that, especially for our community, the LGBT community. And be more reassuring and helpful with that."

- Participant One

Observable signs of trans-knowledgeability and inclusivity.

As reported previously, participants engaged in intentional searches for trans-knowledgeable medical providers, using online search engines as well as “crowdsourcing” recommendations from social media and peers/friends, when possible. Without the advance knowledge that a specific provider is trans-knowledgeable and inclusive, individuals looked for signs of intentional inclusion in waiting room materials, language use, and signage/forms with gendered and assumed information about the types of patients the office serves. Participants universally reported being positively impacted by visible signs of trans inclusion such as flags, stickers, or LGBTQIA+ inclusive signage and language, including marketing materials, research study advertisements and health-related pamphlets. Language used consistently to describe feelings in these kinds of intentionally inclusive environments was often “safe” and “comfortable.” Participant seven reported how knowing a provider is trans-knowledgeable and inclusive through following the pre-appointment process helped them to feel comfortable accessing care:

"I think I knew ahead of time that they were lgbtq friendly, so I automatically was just comfortable with them like right off the bat. I think having that established kind of, feel to them made me comfortable because I was like okay, all the other- or a lot of the other trans people are going here. This is where they’re getting help, so I know for me that this is gonna be helpful for me, to further my transition."

- Participant Seven

Participant three similarly observed:

"The first things that sort of helped put me at ease were, for one thing it was a very professional smooth-running environment. Everyone there really knew what they were doing, it was, everyone was friendly and easy to talk to. All the steps involved of you know filling out paperwork and stuff were very easy and clearly explained, it felt comfortable, safe, that kind of thing. They asked for pronuons and things like that and preferred name which helped as well cuz that let me know that I was in a place where I was going to be respected."

- Participant Three

Self-Perception of Transphobic Incidents

It was noted that during the course of the interview questions, 100% of the participants reported at least one instance of accessing medical care which was considered by the researcher to be uneducated at best and discriminatory at worst, with an overwhelming frequency of reported “inconveniences.” These inconveniences as described by participants included instances of pharmacy employees refusing to use or accept paperwork from a provider with a preferred name or refusing to use utilizing preferred pronouns. Additional examples included being a witness to providers discussing the added stressors of coordinating care between providers and care systems when a patient has a preferred name or a legal name change.

Participant five discusses navigating systems of care after a legal name change resulted in inconsistent and invalid name and identification documents during an emergency room visit:

"I was told that they had to go by their forms in their computers even though my insurance card, my ID, everything else says my correct name. So for the first 20 minutes I was having a panic attack, not about whether or not I could walk and go to work and all these things, but whether or not I was going to spend hours in the ER being dead-named because I couldn’t emotionally take it."

- Participant Five

When explaining the process of accessing healthcare, participants often referenced “having to come out” or correct members of the medical team who assumed or intentionally utilized incorrect or out-of-date names, gender designations and pronouns, and health information related to their transition or status as a transgender person. This process was described as causing significant anxiety (all participants), up to and including panic attacks for some. Participants reported instances of being forced to publicly correct medical providers or team members, such as the following example of participant two discussing experiences with visiting nurses following genital surgery:

"A nurse came into my house and she didn’t know anything about the surgery, didn’t even really know what to be looking for. She just said ‘well I know what infection looks like’ – and she said a couple things that made me cringe and one thing that I really remember is that, she asked me, she was like ‘so, I have a question. Why do some people…’ and she didn’t know the word, and I filled it and was like ‘transition’ and she’s like ‘yeah. just to date the same sex.’"

- Participant Two

Participant one on how dysphoria being triggered creates discomfort:

"It would make a difficult experience if they had to use my legal name and things like that and, just uncomfortable questions about my reproductive health. For sure, asking about my period and things like that and, sex life, even which they don’t really but. Anything that would give me dysphoria."

- Participant One

It is interesting to note, despite 38% of participants directly stating that they had no perceived negative experiences accessing healthcare when asked, 100% of participants ultimately reported at least one incident of disrespect, harassment, and transphobia, up to and including being kept from appropriate medical care, being refused care due to status as a transgender person, being asked inappropriate and unnecessary medical questions regarding the individual’s genitalia or sexual preference, etc.

Experiencing Healthcare as a Privilege and not a Right.

While analyzing the narrative data around the negative and positive experiences had while accessing healthcare, it was found that 63% of participants actively indicated some form of gratitude, or feeling lucky that they had not experienced significant negative experiences, despite 100% having indicated in some part of the interview an interaction or experience that was negative or transphobic as described. This internal perception that they are not only lucky to have not experienced any more significant issues, combined with the realities described by these participants, warrants further study around trauma, mental health, and resilience in transgender adults seeking medical care despite discrimination, micro-aggressions, and occasional outright refusal of care.

Participant Two on being hopeful that the next medical visit won’t be terrifying:

"Just because I don’t know what I’m going to run into, I have had mostly positive experiences, but I’ve also had those negative experiences where it’s terrifying. So, no matter what, I get scared for any kind of medical visit."

- Participant Two

Participant two later in the interview also directly expressed being grateful for the medical care they receive in Massachusetts: “I think Massachusetts is doing a really good job with you know, providing medical care for trans patients, and yeah. I am glad to live where I live.”

Participant three on their experience from a perspective of privilege and appreciation:

"I don’t think my experiences are anywhere near universal because I feel that I’ve been overall very very fortunate and have had generally positive experiences apart from the things that I mentioned. And I’ve heard just talking to friends and loved ones about their experiences and hearing what other people within the trans community go through. I definitely get the sense that positive experiences are much less common than would be preferred. You know it’s usually a lot more difficult for people to receive healthcare in a quick and safe manner, and – oh and also the fact that I also feel it’s important to mention that I think that a lot of that has to do with the fact that I am in a more privileged position given that I am not disabled, I am not a person of color, I am relatively middle class, all of that I think has generally aided me and allowed me to have an overall pleasant experience with healthcare, compared to the people who would not be in these positions."

- Participant Three

Primary Care Relationships

Trends in the data show that strong relationships with trans-knowledgeable primary care providers can help reduce the likelihood of negative healthcare experiences.

(Photo from the Gender Spectrum Collection)

Intentionally Inclusive Healthcare

What does Intentionally Inclusive and trans-knowledgeable medical care look like, and how can we get there?

Self-Identified Transphobia

Participants had interesting perspectives on the negative experiences they had endured while accessing medical care, which often contradicted their perceived transphobia.

(Photo from the Gender Spectrum Collection)

Resources For inclusive transgender healthcare in massachusetts

Patients

Click here for resources on obtaining healthcare in Massachusetts as a trans person curtesy of the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition.

Medical Professionals

Click here for resources on creating a trans-inclusive healthcare environment in medical practices.

Everyone

Click here to submit a question to the author about the study, leave a general comment, or just say hello!