About the Author

Nic Tompkins-Hughes

Nic Tompkins-Hughes, BSW (Honors '20) is a social science researcher, community organizer, and advocate. Nic identifies as transmasculine non-binary and uses they/them pronouns.

Visit Nic's LinkedIn for an overview of their academic and professional experience Here.

Sections

Experiences of Transgender Adults Accessing Healthcare in Massachusetts

Methodology

Development of study materials

This research is an exploratory qualitative study, consisting of semi-structured interviews and utilizing grounded theory to analyze the results and answer to the research question. The researcher developed a seven-question interview survey, using open ended explorative questions. Semi-structured questions involved a primary question, with pre-approved sub-prompts to explore the content of the answer within an open-ended format, while still maintaining similar core areas of discussion (see Appendix A).

A demographic screening survey was developed utilizing the National Center for Transgender Equality’s 2010 and 2015 surveys as a guide. The demographic questionnaire focused on identifying the participant’s age, sex assigned at birth, current gender identity, level of education, level of medical insurance coverage, identity as a transgender person, preferred pronouns, and status of any legal transition processes related to documentation and social changes such as driver’s license and birth certificate name and gender marker changes. The demographic questionnaire also asked a question about chronic or ongoing healthcare needs; however, this was the only question asked about healthcare access or needs in this portion of the interview (see Appendix B).

Recruitment

Following approval by the Bridgewater State University (BSU) Internal Review Board (IRB), recruitment was done using convenience and snowball samples, with a goal of interviewing a minimum of ten individuals from Massachusetts. A recruiting letter was created detailing the voluntary nature of the study, risks, and benefits of participation, and outlining the purpose and intended usage of the data, and the data collection and analysis process (see Appendix E). Due to the student researcher’s identity as a member of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and adjacent/aligning/allied (LGBTQ+) community, as well as a gender non-conforming and transgender identified person, some exiting connections to the community were logical avenues for recruiting and interviewing.

Recruitment occurred between May 27, 2019 and August 1, 2019, with a resulting sample of 8 eligible transgender adults. Criteria for inclusion in the study included: self-identifying as transgender, accessing, and receiving healthcare in Massachusetts, and being age 18 or over. All participants were provided with a written informed consent document approved by the BSU IRB, which was also reviewed verbally (see Appendix C). The student researcher obtained both written and verbal informed consent to participate.

Recruiting involved direct contact, both through face to face discussion, and electronic communication, with transgender individuals from within the student researcher’s geographic and community connections across southeastern Massachusetts. As a member of the community, the researcher also utilized attendance at events focused on the LGBTQ+ community (also referred to as the Queer community) to recruit potential participants. This included engaging with transgender-owned and operated businesses and organizations focused on the support and advocacy of transgender communities and individuals.

The research created a digital recruiting flyer utilizing information and language from the IRB approved recruitment letter, which was shared directly within online communities that the student researcher is active within, with the permission of group leaders and participants (see Appendix E).

Data Collection

Once consent was obtained, participants were provided the IRB approved demographic questionnaire, and engaged in a seven-question interview, which was conducted in a semi-structured qualitative format. The interviews were audio-recorded using a hand-held audio recorder, the audio content of which was immediately uploaded to the researcher’s secure online cloud storage account.

Following the interview, which took approximately 45 minutes, participants were then provided with IRB approved debriefing materials regarding the rights of transgender patients in Massachusetts and the United States. Additionally, contact information and resources for transgender informed mental health supports were provided in the event of any adverse emotional outcomes following the interview, due to the sensitive and traumatic nature of potentially reliving experiences of discrimination (see Appendix D). In appreciation for their involvement in the study, participants were offered a gift of $10 value, which was funded through the Adrian Tinsley Grant for Undergraduate Research through Bridgewater State University.

Data Analysis

The researcher transcribed a total of 247 minutes of audio interviews. As they were completed, interview transcripts were then reviewed and coded utilizing grounded theory and constant comparisons, with line-by-line review of interview content which was labeled based on the emotions, actions, and general information occurring in each line of the interview (Charmaz, 2014). These initial codes were then compiled and pooled into more generalized axial/secondary codes which were found to be applicable across multiple interviews, constituting themes and concepts to be further investigated by the research team (Charmaz, 2014). Data analysis of demographic questionnaire responses was performed also, and trends between the interview data were quantified and analyzed using descriptive analysis and grounded theory, respectively.

Developing theory. With all eight interviews transcribed and coded, the researcher identified emerging themes and patterns of experience, which were then analyzed and explored further within the data comparatively and was also checked against existing study and literature materials relevant to the scope of the study, to determine if the data was sound and reflected existing identified trends of transgender experience.

Demographics

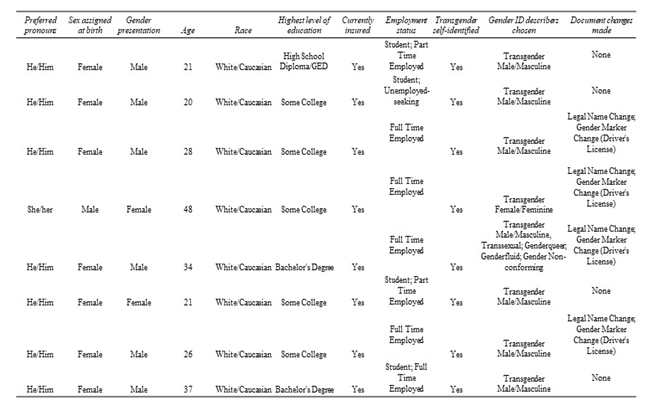

Gender Identity. A total of eight individuals participated in the study, all of whom self-identify as Transgender. Of these, seven were assigned female at birth (AFAB) and further self-identify as Transgender Male/Masculine (Trans-Masculine) (6 out of 7 AFAB participants) and Genderqueer/Gender Non-Conforming (GNC) (1 out of 7 AFAB participants). There was one participant assigned male at birth (AMAB) who self identifies as Transgender Female/Feminine (Trans-Feminine). (see Table 2)

Age, Education and Employment. Study participants ranged in age from 20 to 48, with a mean age of 29.38. All the study participants self-identified as White/Caucasian. When looking at academic achievement, 5 of 8 indicated having completed “Some College” and 2 of 8 indicated completion of a bachelor’s degree. For employment, 5 of 8 participants reported current full-time employment, and 2 of 8 as being employed part-time. Only one participant indicated they were Seeking Employment. Half of the study participants also reported a current student status, separately measured from employment status. (see Table 2)

Healthcare needs. Regarding health care needs, participants were asked “Do you have any medical conditions or concerns which warrant ongoing or regular medical care with a medical provider?” Of note, during interviews it became apparent that due to status as a transgender person, undergoing transition of any kind (biomedical, social, legal) would warrant some degree of ongoing medical care as a requirement; this could include ongoing care to receive letters of medical certification for legal and social transition, or to receive biomedical or social/emotional professional support for any form of transition. This in and of itself may be considered a form of complex care based on the wording of the initial question, however only half of the participants answered this question affirmatively (indicating that this was not a universal unanticipated finding).For the purposes of this study, the ongoing medical needs associated with transition were not considered as an affirmative answer to the question listed above, regarding the need for ongoing medical care for complex healthcare or medical needs. Ultimately, 4 of 8 participants indicated ongoing medical care which was defined as “complex care.” (see Table 2)

Transition and documentation status. When it came to transition itself, all study participants indicated they have pursued a biomedical and/or surgical intervention as a means of easing dysphoria related to their gender identity. Most participants (7 of 8) indicated that they are currently or have at some time been living full-time as their identified gender, during the context of the interview session. Most study participants had completed very few legal or documentation-related transitions. Four out of eight participants indicated that they had completed a legal name change, and the same four indicated completion of a gender marker change on a driver’s license. These four individuals overlapped both categories, however none of the 8 participants had completed a gender marker change on their birth certificate.

All participants indicated that discrepancies between documentations and usages of preferred names, legal names, birth names, and gender markers all created challenges when it came to accessing healthcare, and five participants stated that this discrepancy actively creates dysphoria. In four cases, this inconsistency and the provider’s inability to correctly manage these changes, resulted in the affected individuals receiving inaccurate and/or inappropriate medical care based on their biological needs. A further three participants stated that they typically “pretend” to be a cis individual in order to avoid dysphoria associated with coming out to medical providers. Five participants felt forced to come out to medical providers or members of the medical team in order to address inaccurate documentation, request accurate medical care, or explain medications during encounters, putting them in a confusing and uncomfortable position as the patient and educator, as well as being self-advocate. As reported by Participant 5, “It’s a lot of contradicting people in one appointment, and by the end of it they’re kind of sick of you.”

Overall, study participants were primarily Trans-masculine, (assigned female at birth, transitioning to masculine presentation, and using He/Him pronouns socially when/wherever possible) and in their late twenties (7 of 8). Participants were all white, insured, and were mostly employed, educated and/or currently pursuing education. Half of our study participants indicated formal and legal changes made as a part of their transition, however all participants discussed biomedical and social transition steps taken currently or historically, with an intent to continue to do so indefinitely or at some time in the future when possible. (see Table 2)

Insurance coverage. All study participants reported currently having health insurance coverage, with some participants mentioning challenges with insurance coordination of benefits for transition related medical care. At least one participant did report challenges with insurance companies while attempting to access medical care which was medically indicated for their physical body, but which the insurance company attempted to deny due to a change in the legal gender marker on the participant’s identification and insurance policy. (see Table 2)

Participant five discussed the challenges of having a right to biologically necessary medical care:

Like if you go for a pap smear but you’re registered as male, your insurance bills get bounced back... So, I’ve gotten in multiple arguments with billing people about such things, it’s like no I deserve testosterone and a pap smear, really. I have the right to both of those things, I know it’s confusing, but I should get both. (Participant five)

Table 2

Demographic Results

Previous Section

Next Section

Previous Section

Next Section

Primary Care Relationships

Trends in the data show that strong relationships with trans-knowledgeable primary care providers can help reduce the likelihood of negative healthcare experiences.

(Photo from the Gender Spectrum Collection)

Intentionally Inclusive Healthcare

What does Intentionally Inclusive and trans-knowledgeable medical care look like, and how can we get there?

Self-Identified Transphobia

Participants had interesting perspectives on the negative experiences they had endured while accessing medical care, which often contradicted their perceived transphobia.

(Photo from the Gender Spectrum Collection)

Resources For inclusive transgender healthcare in massachusetts

Patients

Click here for resources on obtaining healthcare in Massachusetts as a trans person curtesy of the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition.

Medical Professionals

Click here for resources on creating a trans-inclusive healthcare environment in medical practices.

Everyone

Click here to submit a question to the author about the study, leave a general comment, or just say hello!